- Home

- Annie Choi

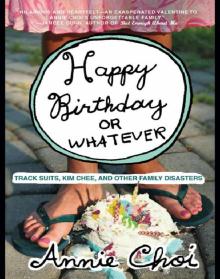

Happy Birthday or Whatever

Happy Birthday or Whatever Read online

HAPPY BIRTHDAY OR WHATEVER

Track Suits, Kim Chee,

and Other Family Disasters

ANNIE CHOI

FOR MY PARENTS

CONTENTS

Happy Birthday or Whatever

Animals

Spelling B+

Crimes of Fashion

Stroke Order

Period Piece

Holy Crap

The Best Diet

Vegetarian Enough

The Devil Moisturizes

Fool Who Play Cool

Rules of Engagement

New Year’s Games

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

HAPPY BIRTHDAY OR WHATEVER

I was going to have the best birthday ever. It would start with a parade—a dizzying spectacle of floats, prancing palominos, and the country’s loudest marching bands. There would be troupes of mimes and contortionists, foul-mouthed drag queens, and a man juggling little girls on fire. Monkeys dressed in powder blue tuxedos would throw candy and tiny bottles of whiskey to the hordes of my fans lined up along Sixth Avenue. A dozen Michael Jackson impersonators, from his pre-op “Rock with You” days to his current noseless incarnation, would handle the sixty-foot helium balloon version of me. As the Grand Marshal, I would ride on the back of an elephant and wave as streamers, confetti, and twenty-dollar bills cascaded over me. After the procession, my friends and I would drink all the liquor in Manhattan, break tequila bottles over our heads, and pick fights with the Hell’s Angels. The next morning we would crawl into work at the crack of noon, nursing hangovers and picking glass out of last night’s clothes, and proclaim that the only birthday that could’ve been more historic was Jesus’ bar mitzvah.

The morning of my twenty-seventh birthday, I received several e-mails from friends sheepishly bowing out of dinner, bar-hopping, and whatever mischief the night might bring. “No problem,” I replied, “more liquor for the rest of us.” Later, two more friends cancelled: “But maybe we’ll make it—call us later tonight.” No matter, I thought, the rest of us can still level every bar in the city. Then another friend explained he was “just too tired.” I called him a geriatric and crossed him off my list. Seeing the members of my posse dwindle, I called my remaining friends to confirm our night of debauchery. One got a last-minute ticket to something that wouldn’t be as exciting as my birthday—Madonna and her fake British accent in concert—and the other didn’t return my calls. A half-hour before party time, other friends decided that meeting deadlines outweighed meeting Jose Cuervo. What would have been a highly intemperate party with twelve of my closest friends ended up being a quiet group of four (myself included) dining at a restaurant where tables were set with too many forks. We split a bottle of wine and ate outside. It was humid. Our waiter scraped breadcrumbs off the tablecloth with a little metal scoop, and the butter, which was sculpted into a tiny rose, sweated in the August evening heat. I turned twenty-seven with no monkeys or trans vestites or celebrity impersonators. And no phone calls from my parents.

The next morning I woke up and checked my messages. Perhaps my parents called in the middle of the night; they live in Los Angeles and the three-hour time difference worked in their favor. Nothing. I was surprised; my parents use the phone as a 3,000-mile-long umbilical cord, and most of the time I want to strangle myself with it. My mother calls just to inform me that rice is on sale at Ralph’s, but it’s still cheaper to buy it at a Korean grocery store and how much is rice in New York and why do Americans eat Uncle Ben’s, when he’s not even Asian (one of the many things about Americans that still confuse my mother even though she and my father immigrated in 1971). On the one day that my parents were supposed to call, they didn’t. Even my brother, the guy who used to wrestle me to the ground and fart in my face, remembered. Mike sent me a characteristically terse e-mail: “Happy birthday or whatever.” My brother, in addition to being a master wordsmith, keeps untraditional hours. He spends his days sleeping and his nights processing loans for a major bank. But even he managed to send his little sister a birthday greeting.

I checked the missed-calls list on my cell phone. Nothing. What kind of parents forget their child’s birthday? Bad ones. Unloving ones. Ones that don’t deserve the World’s Greatest Kid. (I have the mug to prove it; I stole it from my brother.) My birthday should be easy to remember—August 25th, the day before their wedding anniversary.

I toyed with the idea of not calling my parents on their anniversary and playing out a childish drama, but I realized that my parents never made a big deal about their anniversary. They’ve always appreciated my phone call and greetings, but I don’t think they expected it. When I was growing up, August 26th was just another day. But on August 25th, I was the center of everyone’s universe, and the Anniverse included a stuffed animal, my favorite meal (spaghetti or tofu stew), and an ice cream cake from Baskin-Robbins (Jamoca Almond Fudge). I flipped open my phone. At the very least, I could make my parents feel guilty. That could be fun. I dialed my mother first.

“Hello?”

“Hi, it’s me. How are you?”

“Who this?”

I thought that evolution and genetics allowed parents to easily identify the voices of their offspring. This is why wolves can identify their pups by their whines and barks from miles away. My mother apparently opted out of that gene. Instead she got the one that suddenly made her forget the date she squeezed out a squirming eight-pound ball of flesh after spending nine months with an indomitable case of hemorrhoids, which she has always made a point of mentioning to me.

“This is your daughter.”

“Anne?”

“Is there another?”

“Hi, Anne! You sound funny.”

“Maybe a little older? More mature?”

“No. How you are?”

“I’m good. I’m calling to say happy anniversary.”

Silence. I heard scratchy Korean AM radio playing in her car—a commercial for the new, faster Hyundai Sonata. The last time my mother was this quiet it was 1982, and she was heavily sedated after three root canals. She shuffled around the house slowly and groaned, just like a zombie, only with more drool.

“Mom? You there? Happy anniversary.”

“No, today not Mommy anniversary.”

She has always called it “Mommy anniversary.” Evidently it is the day she got married without my father.

“Uh, yes today is your anniversary.”

“No, Mommy anniversary in September.”

“No, your birthday is in September. Dad’s birthday is in September, too. But your anniversary is today.”

“I don’t think so, Anne. You wrong.”

“Trust me, today is your anniversary. Do you know how I know it’s your anniversary?”

“How?”

“It’s the day after my birthday. Which was yesterday, the twenty-fifth.”

Silence again. Ah hah! This was the part where she cried and begged for forgiveness and shipped me an ice cream cake. With two flavors.

“Nooo, Anne, you birthday in September.”

“What? Mom, my birthday is not in September.”

“No, you wrong, Anne, you wrong.”

“You’re kidding, right? Don’t you think I’d know when my own birthday is? Here, let me read you my driver’s license.”

“No Anne, I tell you, you birthday in September. I remember. How I forget?”

I rolled my eyes. My mother can be one smooth-talking and wily lady, but there was no way she could convince me and the Department of Motor Vehicles that my birthday was in September. I fumbled for my wallet.

“Le

t’s see, it says here D-O-B. Do you know what that stands for? Now I don’t have a dictionary handy, but I believe it stands for Date of Birth. So, according to the State of New York, I was born eight/twenty-five/seventy-six. That means my birthday was August twenty-fifth. Yesterday.”

“Yesterday?”

“Yes. Yesterday. You totally forgot.”

“Are you sure?”

“MOM, you forgot. Just admit that you’re wrong and you forgot.”

Silence again. I had her. She was trapped. Now I could taunt her at will—point my finger, make faces, make demands: Bake me some cookies. Take me to Disneyland. Buy me a pony.

“Oh…Anne…Mommy feel…bad. I such…terrible mommy.” She fell quiet again and breathed deeply. I felt a burning twinge in my stomach. I tried to ignore it but it crept up inside me. I hoped that it was acid reflux from last night’s sweaty butter flower, but I knew it was guilt. She didn’t mean to forget. It was just a birthday. No big deal. Plenty of parents all over the world have forgotten their children’s birthdays. John Hughes even made a movie about it. It’s not like my mother didn’t love me. She’s done worse.

“Look, I’m sorry. You know I don’t care, I just like to give you a hard time.” I could hear the soft whir of traffic and the radio. Classical music.

“Oh good! OK. I drive now. Mommy go bye!”

Click.

“Ah, shit!” I snapped my cell phone closed. How the hell did she do it? She wronged me, yet I was the one who’d apologized. She sensed my weakness and moved in for the kill. She is a crafty one, my mother. I simmered. I fumed. I mashed the buttons on my phone and dialed my father’s office. Someone should apologize to me, damnit. The line was busy. My father doesn’t believe in call waiting. I suspected that my mother hung up on me and called him immediately to caution him about their slighted daughter. She’s always one step ahead of me. Five minutes later, I got through to my father.

“Hi, Dad.”

“Oh, Anne, happy birthday! How are you! How’s New York?”

I raised an eyebrow. He seemed too cheerful. I don’t trust cheerful people. They are either elementary-school teachers or axe-murderers or parents who have forgotten something important.

“My birthday was yesterday.”

“I know.”

“So why didn’t you call?”

“I very busy at lab. I mean to call you.”

“You were too busy to call your own daughter on her birthday?” I don’t think my father realized that remembering my birthday and not finding the time to call was actually worse than forgetting altogether. He was lying. He has always been bad at lying. When I was in third grade, my father cut a deal that if I earned straight A’s on my report card, he’d quit smoking. I brought home straight A’s, stuck my report card to the refrigerator, and demanded that he empty his carton into the garbage can. A week later I smelled cigarettes on his clothes. He denied it, even when I pointed to the familiar rectangular lump in his shirt pocket. I was crushed.

“You know, Mom didn’t call me either.”

“Really? Are you sure you not miss message?” I rolled my eyes. He’s not as slick as my mother.

“Oh come on, you both forgot my birthday. Just admit it.”

“I tell you Annie, I not forget. You birthday is day before my anniversary.”

“Did Mom tell you that?”

My father laughed. He was caught. He knew it. “Maybe. Maybe not.”

“Well, happy anniversary. Whatever.”

“And happy birthday to you.”

“It’s too late to say happy birthday.” I pouted. I was six years old again. Except when I was six my parents remembered my birthday.

“You sad, Annie?”

I could sense my father smiling and sulked even more, the way kids get angrier when parents laugh at the cute way they get angry. “No, no I’m not sad. Is there anything else you want to tell me?”

Sorry. My apologies. Excuse me. Forgive me. Please don’t be angry with me, I am a terrible person and I don’t know how I’m going to live with myself with all this guilt and shame and how can I make it up to you? May I interest you in a bucket of cash?

“No, that’s it. I have to work now.”

I hung up. My phone conversations with my father are never more than two minutes long because he’s too busy putting out fires at work—literally. He’s a metallurgical chemist with very little regard for safety. His hands are blistered from open chemicals and flames and part of his yellowed thumbnail is missing. Every shirt he owns is stained and full of holes from acid splatters. His face masks, goggles, aprons, and gloves remain in their original 1980s boxes, with the faded pictures of men in hard hats who are much too excited about safety. When I was eight, he gave me a glass mercury thermometer, which I liked to chew on and wave like a wand. Eventually he remembered that mercury causes mental retardation. When I was sixteen, I bought nail polish remover and Bactine, and my father made me return them, “I have better stuff at lab.” The next day he brought home acetone and hydrogen peroxide in little plastic bottles labeled with their chemical formulas, C3H6O and H2O2. Incidentally, these are the only two formulas I ever got right on my chemistry tests. I guess in the excitement of labeling the bottles, my father forgot to dilute them. The laboratory-strength acetone was so strong it actually took off the nail polish plus the top layer of my fingernails, leaving ten little chalky splotches behind. I didn’t dare try the peroxide. I showed my mother the remains of my fingertips and she shook her head: “You daddy such NERD!”

About two weeks after my parents’ anniversary is my father’s birthday. For a long time, the family celebrated his birthday at El Torito, Sizzler, or if he was feeling fancy, Black Angus. They were all conveniently located within a block of each other, near the mall. We would pile into the car with my father behind the wheel and he’d make a last-minute decision. My brother always lobbied for El Torito and its Conquistador platter, which was a combinación magnífico of everything stuffed, battered, and fried on the menu. After going vegetarian in high school, I became particularly fond of Sizzler, with its generous salad bar and sundae station. I called my mother to remind her and show off the fact that I was a good person—a better person, perhaps even the best. I remembered birthdays. I was a thoughtful daughter and not at all a little brat wanting to be appreciated. No, not at all.

“Hello?”

“Hi Mom, it’s me, your daughter, Annie Choi. Do you remember me? We’ve met a few times.”

“Oh you make Mommy laugh. How I get such funny daughter? I leave Costco now. I buy butter.”

“You went all the way to Costco just to get that? Why didn’t you just go to Ralph’s?” I paused, trying to think of a clever segue. “Do you know what day it is?” Hmm, not so clever.

“I don’t know. Mommy very late for haircut.”

She was en route to her Koreatown hair salon, which has frenetic Korean pop music, slick black furniture, and mirrors on every surface. My mother’s stylist is a wispy young Korean woman with thick fake eyelashes that look a lot like pubic hair. My mother’s salon is supposedly geared toward young Korean hipsters, but it is usually occupied by scheming Korean ladies who sit under heat lamps and discuss their perfect, expensively educated, doctor/ lawyer children. It is here my mother believes she will find me a loving husband who will buy me a German luxury sedan.

“Mom, today is September ninth. Do you know what that means?”

“You birthday?”

“WHAT? My birthday was—”

“—August twenty-sixth, Mommy know. I kidding, Annie. Joke. Oh, you so serious.”

“MOM, August twenty-sixth is your anniversary. I’m the twenty-fifth. You are totally hopeless.”

“Annie, I say August twenty-fifth.”

“That’s a lie—you’re lying, you liar. You said August twenty-sixth. I heard you.”

She laughed, and I heard her golf clubs jostle violently in the back of her S.U.V. My mother refuses to pay attention to lane lin

es in parking lots. She likes to cut across the entire thing, honking and swerving around people and shopping carts that get in her way.

“No, no, I know what I say, Anne. You so silly!”

“Mom, today is September ninth.”

“Yes, I know.”

“Think, what happens on September ninth?

“I told you, Mommy get haircut.”

“No. Something important.”

“I have golf lesson.”

“Uh, not quite. Here is a hint. It starts with a ‘D’ and ends in ‘ad’s birthday.’”

I imagine an MRI of her brain, with a huge black blob taking over everything, except for the sections that control golf and hair care. Surely medical professionals will be puzzled by her gross memory loss, but impressed by her powerful backswing and her lustrous bob.

“I not understand. What you mean?”

“Today is Dad’s birthday. Remember birthdays? They come once a year for each person in our family. His happens to be today. We wouldn’t want to forget his birthday, would we? That’d be horrible. So horrible. I can’t even imagine anything worse.”

She was unresponsive.

“OK, Anne, don’t forget call you daddy and say happy birthday.”

I groaned. I called my father at his lab. “Hi, Dad. Happy birthday!”

“Annie, thank you.”

“See, I remembered. Look how well you raised me, look how thoughtful I am. I hope you’re proud. How old are you?”

“Too old—sixty-one.”

“Hey, you can retire soon.”

“I’ll never retire. Someone has to pay for Mommy golf.” He laughed because he knew it was true.

“Are you doing anything special? El Torito? A parade?”

“What? Who get a parade for birthday? Only Santa Claus get a parade. I want nothing. I want to do nothing. I go home early, watch TV, fall asleep.”

Happy Birthday or Whatever

Happy Birthday or Whatever